When the Government Fails, Don’t Blame the Market

By: Aaron Segal

In the United States, the land of the free, the champion of capitalism, and the pinnacle of innovation, you have to ask your competitors for permission to start a business. Specifically, a business that provides medical treatment to people. If you want to start a legitimate medical operation, you need consent from your biggest competitor, a written form admitting that your area needs your business. You’re smart enough that you don’t need to read an article to see how this could go horribly wrong. However, I’ll tell you why we thought this was a good idea in the first place.

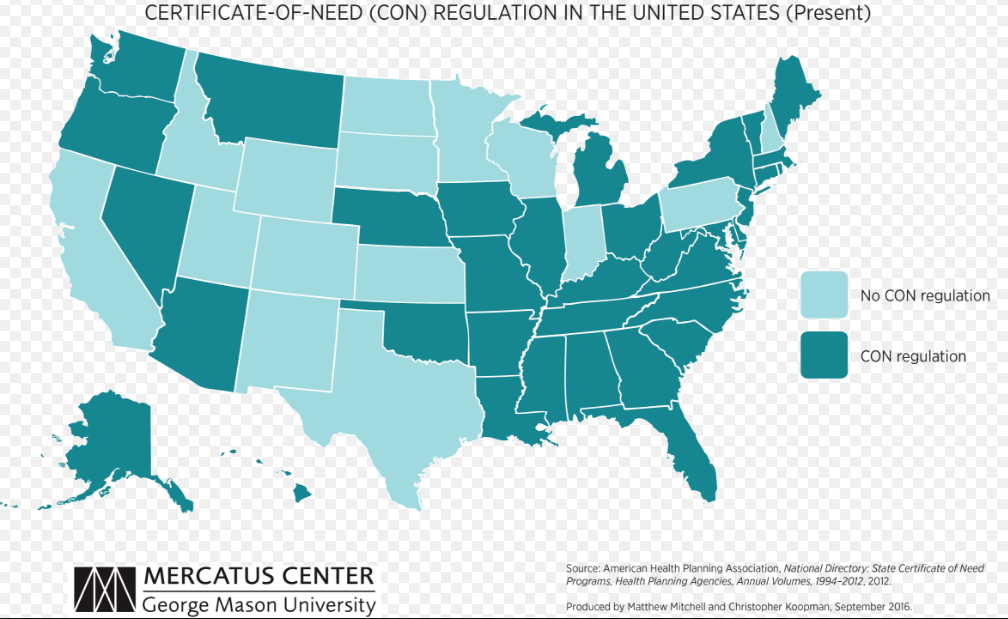

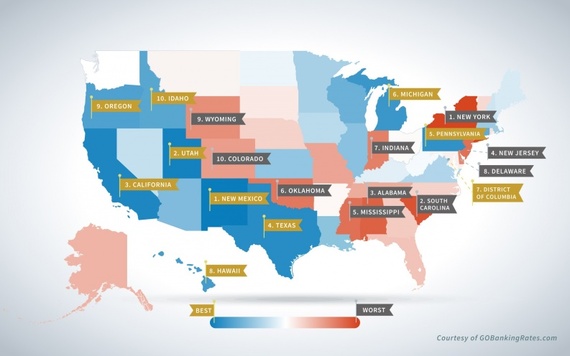

These two pictures listed below are pretty self-explanatory. It appears that, with a few exceptions, states with a CON regulation make the list of highest costs of healthcare, while states without it make the list of lowest costs.

The people of the United States spend more on healthcare than any country in the world. The United States is also responsible for far more biomedical publications and innovations than any country, making up for 40% of the world’s share. And our state of New York has the highest healthcare costs in the entire nation, coupled with mediocre quality. However, the high costs of healthcare do not have to go hand in hand with a system that holds innovation on the highest pedestal, if anything, our innovation should drive prices down. Many argue that allowing companies to follow the profit motive in healthcare is immoral, as no person should profit off of the misfortune of another. This line of logic is absurdly childish, as people voluntarily pay to have their misfortune reduced effectively. Even if a socialized healthcare system existed, people with the ability to pay would still pay for private healthcare that could innovate and had to compete for customers, as long as such an institution would not be made illegal. This is the ideal of healthcare, one in which private entities compete fairly and honestly on the grounds of quality and price, in which a monopolistic company can be unseated by a tiny one that innovates better than it can.

The people of the United States spend more on healthcare than any country in the world. The United States is also responsible for far more biomedical publications and innovations than any country, making up for 40% of the world’s share. And our state of New York has the highest healthcare costs in the entire nation, coupled with mediocre quality. However, the high costs of healthcare do not have to go hand in hand with a system that holds innovation on the highest pedestal, if anything, our innovation should drive prices down. Many argue that allowing companies to follow the profit motive in healthcare is immoral, as no person should profit off of the misfortune of another. This line of logic is absurdly childish, as people voluntarily pay to have their misfortune reduced effectively. Even if a socialized healthcare system existed, people with the ability to pay would still pay for private healthcare that could innovate and had to compete for customers, as long as such an institution would not be made illegal. This is the ideal of healthcare, one in which private entities compete fairly and honestly on the grounds of quality and price, in which a monopolistic company can be unseated by a tiny one that innovates better than it can.

In a truly free market of healthcare one company that refused to offer a cure for cancer and instead gave treatments that eased suffering would be put out of business by a company that found such a cure and sold it. If this company tried to charge exorbitant prices for its cancer-curing drug, a company could think in the long run and put it out of business by selling an improved version of the drug at a lower price. However, every sparkling advantage of a free market healthcare system is thwarted when long-standing healthcare enterprises have special interests in an oversized government. When the government has the power to choose which business succeeds and which fails, this only opens the gateway to companies that cannot succeed on their own merit to make a corrupt deal with the authorities to raise the barrier to entry so that these innovative businesses cannot undercut them and take their market share. In no place is this monstrosity of special interest more prevalent than in the Certificate of Need regulations, one of the greatest causes of inflated healthcare prices in the United States.

These absurd regulations state that for any healthcare facility to expand, acquire new equipment, or merge with other companies, they must pass a need screening, which requires that they prove that their community has a direct need for the services that their growth would offer, and allows locals, government officials, and most frighteningly of all, competitors to testify against their expansion. The initial passage of the CON laws was under the Nixon administration, becoming a requirement for federal funding in 1972. While they lost popularity during the 1990’s due to failure and misuse, they have remained as state law in 35 states despite being removed as a federal requirement and despite countless attempts to remove them by groups ranging from pro-consumer left-wing groups to far-right pro-business ones, and with Bob Lynn, an Alaska politician, acting as a voice for the charge against them. While the initial intent of the CON laws was decent, that any health facility could receive federal funding, and that this was being abused, so a facility would need to prove their necessity to secure this funding, this is no longer the case, and these laws are a vestige that has remained because it supports specific interests that hold power in government.

A reasonable policy would have been to require a CON for funding, or to remove the funding altogether, but stating that making it so less healthcare facilities competing would reduce prices is a total denial of economics and reality. Many of the states without CON’s rank among those with the top cheapest healthcare, and vice versa, with notable exceptions of Wyoming and Oregon. While the CON regulations are framed in such a way that they allegedly keep too many businesses from starting and taking advantage of consumers, it is surreal to think that anyone would believe that there only needs to be as much supply as there is demand. Even if one city only requires a hospital that can treat one hundred patients at a time, there are numerous reasons why another hospital would be necessary and should certainly be allowed. Primarily that, in any sort of crisis, such as an epidemic of disease or the destruction of the main hospital, there would not be enough resources to treat everyone. However, a more realistic reason is much more serious, which is that an excess of supply is necessary to ensure selection. Even if one hospital could hypothetically take care of an entire area, it may not do so with the highest quality or the most competitive prices, in fact, it certainly will not.

To reduce prices, to spark innovation, and to ensure a standard of high quality treatments, a business must always have competition. Even if both hospitals have the capacity to treat the entire population, they both must exist, or even more than two, in order to keep each other from monopolizing the market. As long as there is no barrier to entry, people may always start innovative businesses to shatter monopolies. The problem with these monopolies is that regulations such as the CON keep companies from forming and growing to force them to be competitive. If we had a federal repeal of all CON policies, I believe that healthcare prices would massively drop, especially in states like New York, which has the highest costs of healthcare in the entire nation, and that quality would massively improve. To understand the repugnant corruption present in CON regulations and their administration, one must only view the situation of Dr. Mark Monteferrante, who had to spend $175,000 in legal fees and wait five years just to obtain a second MRI machine, as competitors and the public did not think he had a need for it. The same thing happens across the country when a long standing company can decide which companies can grow and which ones cannot.

The criticisms of healthcare that are often blamed on capitalism are generally attributable to the government’s service to special interests, which is clear here, and certainly not the fault of capitalism, but of a corrupt and overgrown government. The criticism that the profit motive keeps cures and cheap healthcare from being obtained is only valid when the profit motive is coupled with regulations like the CON laws, as the companies that provide this cheap health care and innovation could be shut down by a jealous competitor with the right connections. We can only hope that these regulations are repealed before they shut down the company that could cure cancer or heart disease.